Cluster Mempool1 is a complete reworking of how mempool handles organizing and sorting transactions, conceptualized and implemented by Suhas Daftuar and Pieter Wuille. The design aims to simplify the overall architecture, better align transaction sorting logic with miner incentives, and improve the security of second-layer protocols. It was merged into Bitcoin Core in PR #336292 on 25 November 2025.

The mempool is a huge set of pending transactions that your node needs to keep track of for a number of reasons: fee estimation, transaction replacement validation, and block construction if you’re a miner.

This is a lot of different goals for a single function of your node for service. Bitcoin Core up to version 30.0 organizes the mempool in two different ways to help aid these functions, both from the relative point of view of any given transaction: combined feerate, which looks forward to the transaction and its children (descendant feerate), and combined feerate, which looks backward to the transaction and its parents (ancestor feerate).

These are used to decide which transactions to remove from your mempool when it is full, and which to include first when constructing a new block template.

How is my Mempool managed?

When a miner decides whether to include a transaction in their block, their node looks at the transaction and any ancestors that need to be confirmed first for it to be valid in a block, and looks at the average fee rate per miner. byte across all of them considering the individual fees they paid as a whole. If this group of transactions fits within the block size limit while outperforming others in fees, it is included in the next block. This is done for each transaction.

When your node decides which transactions to remove from its mempool when it is full, it looks at each transaction and any children it has, and removes the transaction and all of its children if the mempool is already full with transactions (and their descendants) paying a higher fee.

Look at the above sample graph of transactions, feerates are shown as such in brackets (ancestor feerate, descendant feerate). A miner looking at transaction E is likely to include it in the next block, a small transaction that pays a very high fee with a single small ancestor. But if a node’s mempool was getting full, it would look at transaction A with two big children paying a low relative fee and probably throw it away or not accept and keep it if it was just received.

These two placements, or ordering, are completely at odds with each other. The mempool should reliably propagate what miners will mine, and users should be confident that their local mempool is accurately predicting what miners will mine.

The mempool working this way is important for:

- Decentralization of mining: getting all miners the most profitable set of transactions

- User reliability: accurate and reliable fee estimates and transaction confirmation times

- Second-layer security: reliable and accurate execution of second-layer protocols’ on-chain enforcement transactions

The current behavior of the mempool does not fully match the reality of mining incentives, creating blind spots that can be problematic for second-layer security by creating uncertainty about whether a transaction will reach a miner, as well as pressure for non-public broadcast channels for miners, potentially exacerbating the first problem.

This is particularly problematic when it comes to replacing unconfirmed transactions, either simply to encourage miners to include a replacement earlier, or as part of a second-layer protocol enforced on-chain.

Replacement according to the existing behavior becomes unpredictable, depending on the shape and size of the web of transactions that your is caught in. In a simple, fee burdening situation, this can fail to propagate and replace a transaction, even when mining the replacement would be better for a miner.

In the context of second-layer protocols, the current logic allows participants to potentially have necessary ancestor transactions kicked out of the mempool or make it impossible for another participant to submit a necessary child transaction to the mempool under the current rules due to child transactions created by the malicious participant or the postponement of necessary ancestor transactions.

All of these problems are the result of these inconsistent inclusion and exclusion rankings and the incentive shifts they create. Having a single global ranking would solve these problems, but it is impractical to reorganize the entire mempool globally for each new transaction.

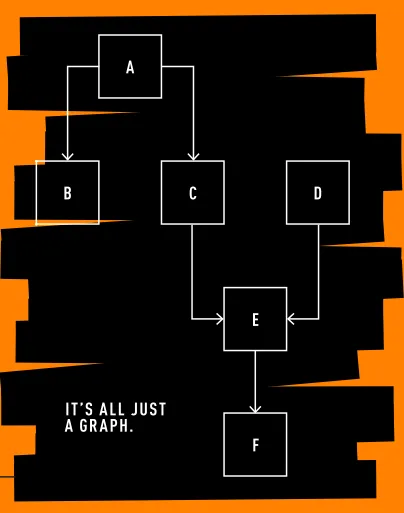

It’s all just a graph

Transactions that depend on each other are a graph or directed series of “paths”. When a transaction uses output created by another in the past, it is associated with the previous transaction. In addition, when it uses the output created by another previous transaction, it connects both of the historical transactions.

When unverified, chains of transactions like this bowl get the previous transactions confirmed first so that the later ones are valid. After all, you can’t use output that hasn’t been created yet.

This is an important concept to understand the mempool, it is explicitly ordered directional.

It’s all just a graph.

Chunks Make Clusters Make Mempools

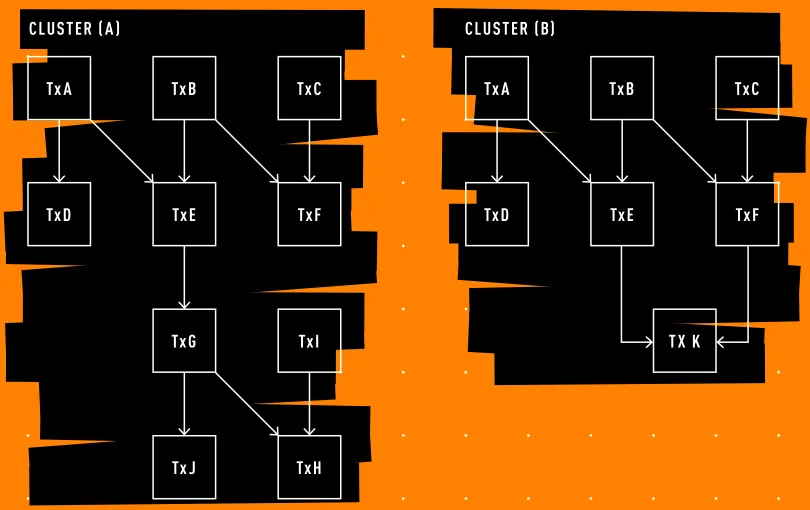

In cluster mempool, the concept is one cluster is a group of unconfirmed transactions that are directly related to each other, i.e. consumption output created by others in the cluster or vice versa. This will be a fundamental unit of the new mempool architecture. Parsing and ordering the entire mempool is an impractical task, but parsing and ordering clusters is much more manageable.

Each cluster is divided into bitssmall sets of transactions from the cluster, which are then sorted in order of highest fee rate per byte to lowest, while respecting the direction dependencies. So, for example, let’s say from highest to lowest feerate that the chunks in cluster (A) are: [A,D], [B,E], [C,F], [G, J]and finally [I, H].

This allows pre-sorting of all these chunks and clusters and more efficient sorting of the entire mempool in the process.

Miners can now simply grab the highest feerate chunks from each cluster and put them into their template, if there is still room they can go down to the next highest feerate chunks, continue until the block is roughly full and just need to figure out the last few transactions it can fit. This is roughly the optimal block template construction method, assuming access to all available transactions.

When nodes’ mempools get full, they can simply grab the lowest feerate chunks from each cluster and start evicting them from their mempool until it’s not over the configured limit. If that wasn’t enough, it moves on to the next lowest feerate bits, and so on until it’s within its mempool limits. Done this way, it removes weird edge cases out of alignment with mining incentives.

The replacement logic is also drastically simplified. Compare cluster (A) with cluster (B) where transaction K has replaced G, I, J and H. The only criteria to be met is the new chunk [K] must have a higher chunk feerate than [G, J] and [I, H], [K] must pay more in total fees than [G, J, I, H]and K cannot exceed an upper limit on how many transactions it replaces.

In a cluster paradigm, all these different uses are consistent with each other.

The new Mempool

This new architecture allows us to simplify transaction group limits by removing previous limits on how many unconfirmed ancestors a transaction can have in the mempool and replacing them with a global cluster limit of 64 transactions and 101 kB per cluster.

This limit is necessary to keep the computational cost of presorting the clusters and their chunks low enough to be practical for nodes to execute on a constant basis.

This is the real key insight into cluster mempool. By keeping the lumps and clusters relatively small, you simultaneously make the construction of an optimal block template cheap, simplify the transaction replacement logic (fee-bumping), and therefore improve second-layer security and fix eviction logic all at once.

No more expensive and slower calculations for template building or unpredictable fee-bumping behavior. By correcting the misalignment of incentives in how the mempool managed the transaction organization in different situations, the mempool works better for everyone.

Cluster mempool is a project that has been years in the making and will have a significant impact on ensuring that profitable block templates are open to all miners, that second-layer protocols have sound and predictable mempool behavior to build upon, and that Bitcoin can continue to function as a decentralized monetary system.

For those interested in diving deeper into the nitty-gritty of how cluster mempool is implemented and works under the hood, here are two Delving Bitcoin threads for you to read:

High level implementation overview (with design rationale): https://delvingbitcoin.org/t/an-overview-of-the-cluster-mempool-proposal/393

How Cluster Mempool Feerate Charts Work: https://delvingbitcoin.org/t/mempool-incentive-compatibility/553

Don’t miss your chance to own The core problem — with articles written by many core developers explaining the projects they themselves work on!

This piece is the letter from the editor in the latest print edition of Bitcoin Magazine, The Core Issue. We share it here as an early look at the ideas explored throughout the issue.

[1] https://github.com/bitcoin/bitcoin/issues/27677

[2] https://github.com/bitcoin/bitcoin/pull/33629