The nuclear industry is in the throes of a renaissance. Old facilities are being renovated and investors are showering startups with cash. In the last few weeks of 2025 alone, nuclear startups raised $1.1 billion, driven largely by investor optimism that smaller nuclear reactors will succeed where the broader industry has recently stumbled.

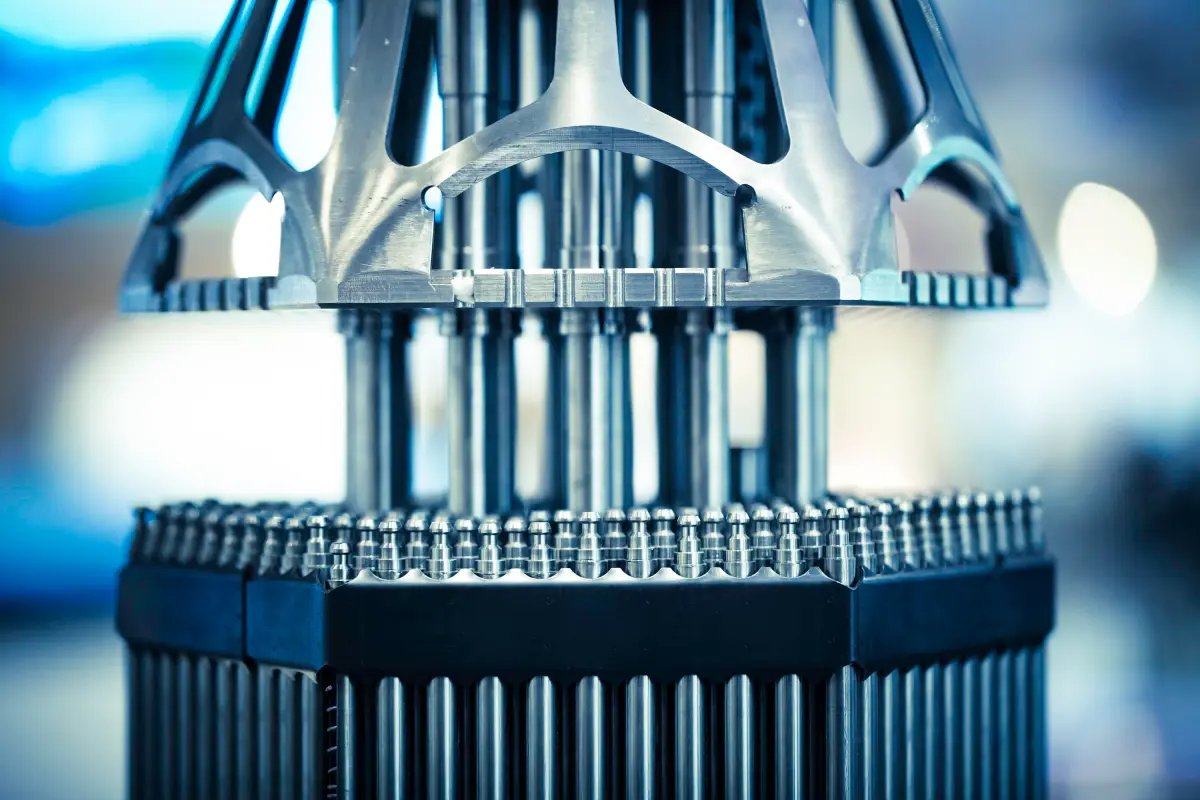

Traditional nuclear reactors are massive pieces of infrastructure. The newest reactors built in the United States – Vogtle 3 and 4 in Georgia – contain tens of thousands of tons of concrete, are fueled by fuel assemblies 14 feet high and generate over 1 gigawatt of electricity each. But they were also eight years late and more than $20 billion over budget.

The fresh crop of nuclear startups hope that by shrinking the reactor they will be able to sidestep both problems. Do you need more power? Just add more reactors. Smaller reactors, they argue, can be built using mass-production techniques, and as companies produce more parts, they should get better at making them, which should push costs down.

The size of that benefit is something experts are still researching, but today’s nuclear startup relies on it being greater than zero.

But manufacturing is not easy. Just look at Tesla’s experience: The company struggled mightily to profitably produce the Model 3 in large numbers — and it had the advantage of being in the auto industry, where the U.S. still has significant expertise. American nuclear startups do not have that advantage.

“I have a number of friends who work in the nuclear supply chain, and they can rattle off like five to ten materials that we just don’t make in the U.S.,” Milo Werner, general partner at DCVC, told TechCrunch. “We have to buy them overseas. We’ve forgotten how to make them.”

Werner knows a thing or two about manufacturing. Before becoming an investor, she worked at Tesla leading new product introductions, and before that she did the same at FitBit, where she launched four factories in China for the wearables company. Today, in addition to investing in DCVC, Werner co-founded the NextGen Industry Group, which works to promote the adoption of new technologies in the manufacturing sector.

Techcrunch event

San Francisco

|

13.-15. October 2026

When companies of any size want to manufacture something, they face two main challenges, Werner said. One is capital, which is often the biggest constraint, as factories are not cheap. Fortunately for the nuclear industry, that shouldn’t be much of a problem. “They’re awash in capital right now,” she said.

But the nuclear industry is not immune to the other challenge that all manufacturers face, a lack of human capital. “We haven’t really built any industrial facilities in 40 years in the United States,” Werner said. As a result, we have lost muscle memory. “It’s like we’ve been sitting on the couch watching TV for 10 years and then getting up and trying to run a marathon the next day. It’s not good.”

After decades of offshoring, the US lacks people who have experience in both factory construction and operations. “There are certainly some people in the United States who have done this, but we don’t have the number of people that we need to all have a full staff of experienced production people.” She’s not just talking about machine operators, but everyone from factory floor managers right up to CFOs and board members.

The good news is that Werner sees a lot of startups, nuclear and otherwise, building early versions of their products close to their technical teams. “It pulls production closer to the U.S. because it allows them to have that cycle of improvement.”

To reap the benefits of mass production, it’s helpful for startups of all stripes to start small and scale up. “Really leaning into modularity is very important to investors,” she said. The modular approach helps companies start producing small quantities early so they can collect data about the manufacturing process. Ideally, this data will show improvement over time, which can reassure investors.

The benefits of mass production do not come overnight. Companies will often predict cost reductions that can result from learning through manufacturing, but this may take longer than they expect. “Often it takes years, like a decade, to get there,” Werner said.